This is a special report, a look behind the headlines at a region defined by ancient rivalries and modern proxy wars. We are witnessing not just a border dispute, but a seismic realignment of power in South Asia, where the growing conflict between Pakistan and the Taliban is forcing new friendships and drawing in the world’s great economic and military powers.

For centuries, Afghanistan has been known as the “graveyard of empires”. Today, it remains caught between ideological extremism and the competing interests of international players. But the latest chapter in this tumultuous history is shocking: a bloody, low-intensity war has erupted between two former ideological allies, Pakistan and the Taliban regime in Kabul, dramatically reshaping the geopolitical map of Eurasia.

In the space of just 48 hours, the tense relationship across the disputed 2,600-kilometer Durand Line disintegrated into open warfare, resulting in dozens of casualties and sealed borders. This confrontation, which saw the use of artillery and intense clashes in at least six or seven border provinces, is more than a simple border skirmish; it is a manifestation of the complex, global hybrid war playing out between competing blocs.

Let us begin with the events on the ground, before examining the high-stakes diplomatic theater that has recently unfolded from New York to St. Petersburg, and how America’s renewed focus on the region is fueling the fire.

The friction between Islamabad and Kabul, while always simmering, accelerated violently in October 2025. The crisis hinges on the presence of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), or “Pakistani Taliban”—a militant group whose goal is to overthrow the Pakistani government and establish an Islamic Emirate in Pakistan. Although ideologically akin to the Afghan Taliban, the TTP focuses its fight against the Pakistani state.

The violent escalation began on Thursday, October 10, when, according to Pakistani security sources, the Pakistani Air Force allegedly conducted an air raid on Kabul, targeting a TTP leader. While the TTP denied that its leader, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, was killed, the Afghan government immediately accused Pakistan of violating its sovereign airspace.

The TTP, seemingly unintimidated, responded fiercely on Friday, October 11, claiming a series of attacks in northwest Pakistan that left 20 security force members and 3 civilians dead.

The climax arrived on Saturday night, October 11, when the Afghan Taliban launched its official retaliation. Forces of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan carried out operations against Pakistani forces along the disputed Durand Line. Afghan Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid stated that 58 Pakistani soldiers were killed and 30 others wounded, while 20 Pakistani security outposts were allegedly destroyed. The Afghan side admitted to sustaining casualties, with nine soldiers martyred and 16 wounded. The defense ministry in Kabul declared the action a direct retaliation for the earlier raids.

Following the intense fighting, which the Afghan side claimed was halted at midnight following requests from concerned intermediaries, including Qatar and Saudi Arabia, the consequences were immediate and severe. Islamabad ordered the closure of all main border crossings, including Torkham and Chaman, effectively strangling Afghanistan’s already fragile, landlocked economy by blocking the transit of goods and people.

For Pakistan, the TTP poses an existential security threat, and Islamabad accuses the Afghan Taliban of hosting and protecting TTP leaders, allowing them to use Afghan territory as a safe base for launching cross-border attacks. Indeed, the TTP’s upsurge in attacks over the past three years has been the fiercest in a decade. For years, Pakistan had played an ambiguous role, often supporting the Afghan Taliban, but now it finds itself facing a hostile neighbor that is either unwilling or unable to control Islamabad’s sworn enemies. The return to power of the Afghan Taliban in 2021 actually strengthened the TTP, which now feels protected by a “brother” government.

Kabul, however, vehemently denies these allegations, asserting that it will not allow its territory to be used to “threaten or harm others”. Instead, the Afghan Taliban has launched counter-accusations. Spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid claimed that the rival terrorist group ISIS-K was defeated in Afghanistan and subsequently established training centers in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. Mujahid alleged that recent ISIS-K attacks in Afghanistan, Iran, and Moscow were planned from these KP bases, demanding that the Pakistani government hand over key ISIS-K members to the Islamic Emirate. In a show of rising tension, the Afghan Taliban rejected a Pakistani request to send a delegation in the wake of the airstrikes.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. This border conflict, seemingly localized, is deeply intertwined with the maneuvers of global powers seeking strategic advantage in Central and South Asia.

As the conflict flared along the Durand Line, the world powers were engaging—or disengaging—with Afghanistan’s de facto rulers in major diplomatic arenas.

During the UN General Assembly general debate in September 2025, no Afghan delegation was present due to the unresolved issue of the UN seat. However, Afghanistan was far from forgotten. The presidents of Central Asian nations used the platform to project a collective doctrine of “managed engagement without recognition”.

Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev urged the international community to “prevent [Afghanistan’s] isolation” and called for support to develop vital transport and energy corridors, such as the Trans-Afghan railway and the Surkhan–Pul-i-Khumri power line. For Tashkent, a southern outlet to Pakistani ports via Afghanistan is critical to transforming from landlocked to land-linked. Other leaders echoed this pragmatic approach: Kazakhstan stressed “inclusive development” for regional stability, while Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov demanded that roughly $9 billion in frozen Afghan central-bank assets be returned to the Afghan people, publicly challenging Western isolation policy. Tajikistan also focused on the urgent need for humanitarian assistance following recent natural disasters.

This doctrine reflects the region’s shared goal: refusal to let Afghanistan collapse, even if formal recognition is off the table.

Meanwhile, the Taliban continues to seek international legitimacy and economic relief by engaging with multipolar partners. Five days before he visited India, the Afghan Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi had traveled to Moscow to attend the Moscow Format Dialogue, underscoring the Taliban’s “balanced and economy-centered” foreign policy. This strategy aims to overcome international isolation by engaging diverse partners like Russia, China, and now India, while refusing to trade domestic policies (such as restrictions on girls and women) for formal recognition.

Perhaps the most potent geopolitical pressure point involves the United States’ desire to return to Afghanistan. President Donald Trump has reaffirmed his goal of restoring US troops to Afghanistan’s strategic Bagram Airbase. Trump had earlier demanded control of Bagram and threatened “bad things” if his demand was not met.

The Taliban, however, has been categorical in its rejection, asserting that Kabul will not accept any foreign military presence and will “never agree to bargain away or hand over any part of our country”.

For the U.S. administration, the motivation for reclaiming Bagram is multi-faceted: it offers a convenient vantage point for observation of China (less than 800 km away from the border), serves as an access point to Afghanistan’s vast reserves of rare earth minerals, and could act as a base for counter-terrorism efforts against groups like ISIS. Russian analysis suggests that the drive to return to Bagram is designed to threaten nearby Chinese nuclear sites, a maneuver that would require the cooperation of Pakistan.

The crisis between Pakistan and Afghanistan is taking place against the backdrop of a broader geopolitical struggle that pits a revitalized US-Pakistan alliance against the regional multipolar processes championed by Russia, India, Iran, and China—key BRICS members!

Pakistan has been rapidly pivoting towards the West since the April 2022 “post-modern coup” that deposed former Prime Minister Imran Khan. This trend has accelerated dramatically since Trump’s return to power. The rapid rapprochement aims to geostrategically reshape South Asia via the revival of its Old Cold War-era partnership, which would advance US interests by greatly decelerating regional multipolar processes.

This strategic revival is evident in Pakistan’s latest overtures to Washington. Pakistan is reportedly offering the US a commercial port in Pasni. This town is near Gwadar, the terminal point of the Belt & Road Initiative’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The proposal explicitly plays on US fears about Iran, Russia, and the prospect of Gwadar hosting the Chinese Navy. A US presence in Pasni could aid the export of minerals, but it is expected to quickly take on military dimensions, serving to counterbalance Gwadar and expand US influence in the Arabian Sea and Central Asia.

If Pakistan completes its pro-Western pivot by fully restoring its Old Cold War-era partnership, the regional multipolar forces would be challenged like never before, potentially leading to them cooperating like never before, with Pakistan bearing the brunt of their collective pressure.

The geopolitical machinations around Afghanistan and Pakistan are deeply rooted in the global trade war, particularly over critical resources. The United States is actively seeking access to Afghanistan’s rare earth minerals, which are crucial for advanced defense technologies. Afghanistan holds vast, untapped potential, sitting on estimated reserves of iron ore, copper, and rare earth elements such as neodymium and lanthanum.

In parallel, China has escalated the trade war, imposing its strictest rare earth and permanent magnet export controls to date. China dominates the sector, accounting for approximately 70% of rare earth mining and 93% of magnet manufacturing globally. These new restrictions target foreign defense supply chains, largely denying export licenses to companies affiliated with foreign militaries (including the US) starting December 1, 2025.

This conflict creates a desperate need for the US to secure alternative supply chains. However, China is currently leading the geopolitical race for Afghanistan’s minerals, signing multi-billion-dollar contracts and securing investments from countries like Qatar, Turkey, and Iran. China’s strategy links these investments, such as the Mes Aynak copper mine, directly to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to enhance global influence and project regional power. Russian analysts suggest the timing of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border clashes, occurring alongside escalating US-China trade tensions (including new 100% tariffs on China), suggests a calculated move by Washington to create a new flashpoint on China’s borders, jeopardizing Chinese infrastructure projects in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The revival of the US-Pakistan strategic partnership and President Trump’s recent punitive actions have provoked a powerful strategic response from India, a key member of the multipolar bloc.

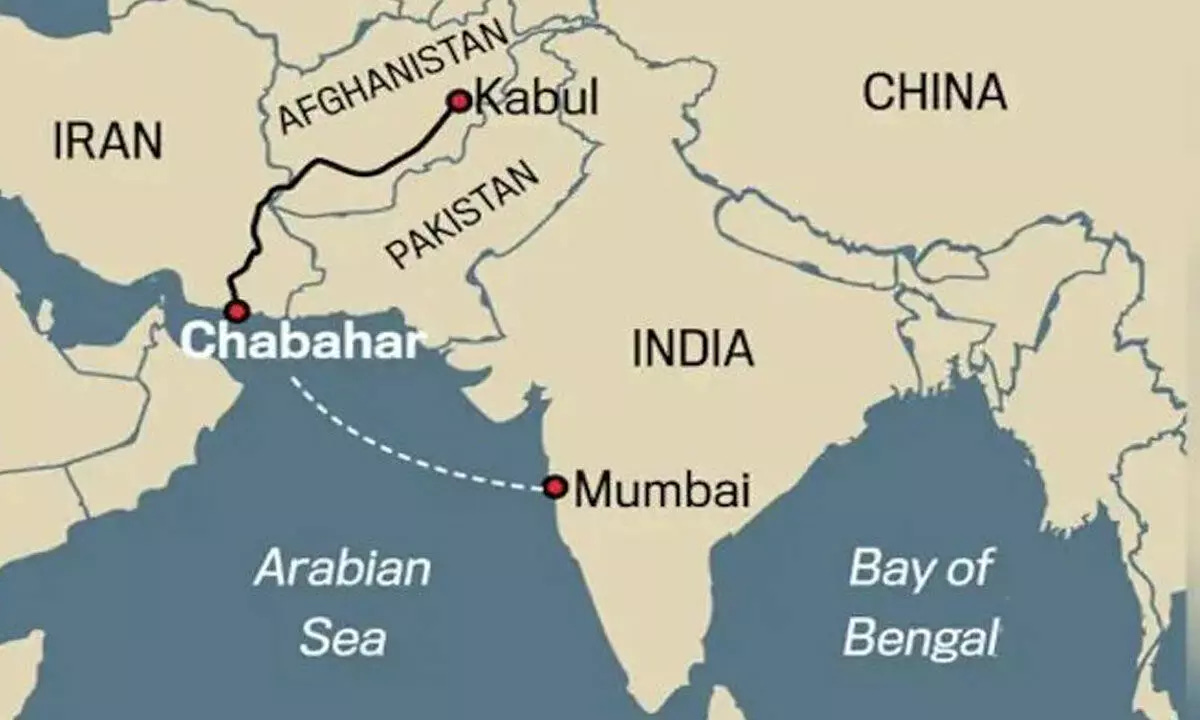

President Trump recently revoked India’s exemption from US sanctions related to the Iranian Chabahar Port, demanding that Indian firms exit the project within 45 days or face losing access to US assets. Chabahar is strategically vital for India as it represents the only route to Afghanistan and Central Asia that bypasses Pakistan. India has invested $370 million and signed a binding 10-year management deal (until 2034).

New Delhi has refused to back down, viewing this action as “blatant economic coercion” and a stark reminder that de-dollarization and a BRICS-led financial system are “urgent necessities”. India remains committed to Chabahar’s future, as it is a key segment of the North–South Transport Corridor linking India to Russia and Europe.

In a “seismic shift” of regional diplomacy, India is simultaneously forging closer ties with the Taliban regime, a move expedited by the deteriorating security relationship between the Taliban and Pakistan.

This rapprochement was formalized during the six-day visit of Afghan Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi to New Delhi. External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar announced that India would upgrade its Technical Mission in Kabul to the status of a full-fledged Embassy. Muttaqi’s visit, the first high-level visit since the 2021 Taliban takeover, marks India’s attempt to reclaim influence and avoid being left behind as rivals like China and Pakistan make inroads in Kabul.

During the meeting, Muttaqi welcomed the upgrade, emphasizing the shared need for enhanced trade via the Chabahar route, and called for joint talks with America to remove sanctions obstacles. Muttaqi also urged India and Pakistan not to mix economic issues with political ones, requesting the opening of the Wagah border route—the shortest and cheapest path for India-Afghanistan trade.

Jaishankar, while not naming Pakistan, stressed the “shared threat of cross-border terrorism” and urged Muttaqi to coordinate efforts to counter this danger. India also announced new developmental and humanitarian aid, including plans to construct residences for Afghan refugees forcibly returned from Pakistan, describing Afghanistan as a “contiguous neighbour”.

This bold diplomatic move, which brings together two historically opposed entities, is widely viewed as a direct consequence of the revived US-Pakistan strategic partnership, which India (and Russia) blame for regional destabilization. The new India-Afghanistan axis strengthens India’s foothold in a contested region, providing access to Central Asia and challenging Pakistan’s regional dominance, creating a scenario of strategic encirclement for Islamabad.

What we are left with is a complex, delicate equilibrium. The military confrontation between Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban is both a cause and a result of the larger hybrid war. Whether driven by geopolitical grand strategy or raw economic necessity, every player—from Washington and Beijing to Islamabad and New Delhi—is now calculating their next move based on the blood being spilled along the disputed Durand Line. The fate of South Asia may rest on whether managed engagement can prevail over escalating conflict.