The narrative surrounding the €210 billion ($245 billion) in immobilized Russian central bank assets began in earnest shortly after the Russian “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine in February 2022, when Western allies globally banned transactions with Moscow’s financial institutions. What started as a decisive measure to impose economic pain has since morphed into a high-stakes, internal European melodrama, replete with legal acrobatics, grandstanding politicians, and the quiet fear of Moscow’s promised retribution.

As this drama unfolded chronologically, 2025 became the year the European Union (EU) decided it was time to move beyond simple immobilization and into the realm of financial alchemy, aiming to transform Russia’s frozen sovereign wealth into Ukraine’s future financing.

By early 2025, the initial shock had worn off, and the reality of Ukraine’s colossal financial needs—estimated by the IMF at €135 billion for 2026 and 2027—forced the EU to find a means to sustain Kyiv. The EU leadership, having committed to covering Ukraine’s financial needs for the coming years, began drafting solutions.

In January 2025, Latvia provided a localized example of asset repurposing, though on a much smaller scale, when the Saeima approved transferring the ‘Moscow House’ in Riga to state ownership, with the proceeds from its eventual auction earmarked for Ukraine support. This signaled a willingness, at least among the more aggressive member states, to convert Russian property into aid directly. Meanwhile, by August, Russian corporate entities were feeling the pinch, as assets belonging to the Turkish Stream operator (South Stream Transport), which has ties to Gazprom, remained under arrest in the Netherlands, tied up in litigation dating back to the 2015 nationalization of energy assets in Crimea.

The political momentum for a large-scale solution intensified in September 2025 when German Chancellor Friedrich Merz first outlined a proposal for a €140 billion loan backed by the frozen Russian assets. This plan was quickly embraced by the European Commission (EC) as a solution that wouldn’t “directly hit the pockets of EU taxpayers”.

By November 2025, EC President Ursula von der Leyen presented member states with two primary options to fund Ukraine: EU borrowing guaranteed by the EU budget (requiring unanimity), and the now infamous “Reparations Loan,” leveraging the cash balances of immobilized Russian assets (requiring only a qualified majority). The proposed Reparations Loan would cover roughly two-thirds of Ukraine’s financial requirements, approximately €90 billion.

Von der Leyen, determined to prove the EU’s stamina against Russian aggression, framed the proposal as necessary to equip Ukraine to “lead peace negotiations from a position of strength” and to “increase the cost of Russia’s war of aggression”. Moscow, of course, had a different interpretation.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, just days after the proposals were made public, dismissed the plan as “theft” of others’ property. He warned that any confiscation would “dramatically reduce” confidence in the Eurozone and instructed his government to prepare a package of “tit-for-tat measures” in retaliation.

As the December 18 EU summit deadline approached, the entire geopolitical chess match devolved into a desperate attempt by Brussels and Berlin to convince a single, reluctant partner: Belgium.

Belgium is the unwilling host of the €185 billion majority of the frozen funds, held by the Brussels-based financial clearinghouse, Euroclear. Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever became the outspoken, cautious voice of reason—or, depending on one’s perspective, the geopolitical wet blanket.

De Wever consistently argued that using frozen sovereign assets during an ongoing conflict is “unprecedented” and a matter usually addressed only in post-war settlements. In his assessment, the legal reality meant the plan was “untenable under current conditions”. He stressed that he “cannot imagine the European Commission confiscating assets from a private company, Euroclear, against the will of a member state”.

The core of Belgium’s objection is understandable: financial terror. Bearing potential legal claims of €140 billion from Moscow—an amount equaling one-third of the country’s annual GDP—would be catastrophic. De Wever categorically refused to “bear financial risks amounting to hundreds of billions of euros” alone.

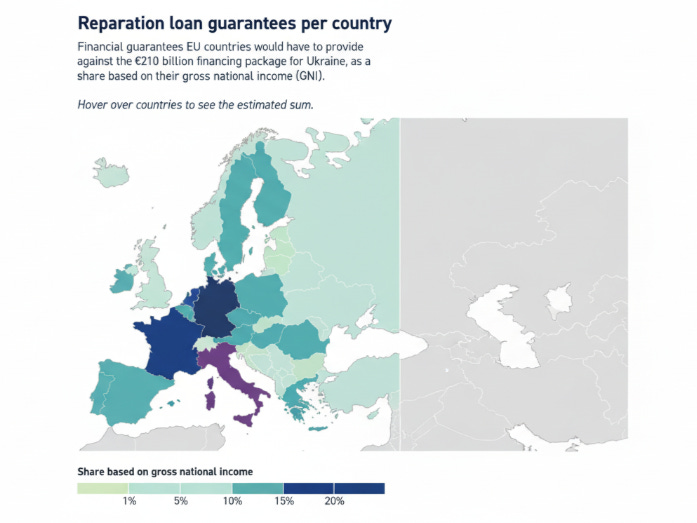

The EC and Germany tried desperately to assuage these fears by introducing “strong safeguards” and a “solidarity mechanism” backed by national guarantees or the EU budget. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, who committed Germany to providing 25% of the backstop (up to €52 billion), insisted that all European states must bear the same risk. Despite a “constructive exchange” with Merz and Von der Leyen on December 6, De Wever remained unpersuaded, reiterating that his conditions were unchanged.

Belgium’s financial sector fully backed this resistance. The banking federation Febelfin warned that if investors feared assets could be seized too easily, the proposal posed an “unpredictable risk to the stability of Belgium as a country” and could trigger capital flight, thus undermining trust in European financial markets.

The Ukrainian response to De Wever’s caution was immediate and biting. Ukrainian officials labeled his stance “deeply immoral,” questioning how he could “defend the rule of law” while simultaneously giving “full impunity for committing genocide” to a nuclear power.

The push for the Reparations Loan quickly exposed deep fissures across the EU.

Hungary, cleverly, never one to miss an opportunity to derail EU craziness, vetoed the alternative plan—the joint EU borrowing scheme—on Friday, December 6. This veto effectively pushed the EC back onto the contested Reparations Loan, which conveniently only requires a qualified majority vote. One might note the delicious irony of Hungary forcing the EU down the path of controversial seizure rather than joint debt, simply because they despise providing further aid to Kyiv, which Prime Minister Viktor Orban compared to “trying to help an alcoholic by sending him another crate of vodka”.

France, meanwhile, offered qualified support, displaying the characteristic Gallic flair for complex compromise. Paris supports the Reparations Loan backed by Euroclear assets, but it adamantly refused to include the €18 billion held in its own private banks, the second-highest private holding in Europe. French officials cited different contractual obligations for private banks compared to the depository Euroclear, effectively drawing a line to protect their own financial institutions from Moscow’s promised retribution.

Amidst this internal chaos, the European Commission, refusing to acknowledge defeat, began looking for procedural shortcuts. Reports on December 8 suggested EU officials were exploring an “emergency” power clause that might allow the decision to be rammed through without unanimous consent, ensuring the December 18 deadline can be met, even if some countries resist.

Adding another layer of geopolitical intrigue, the United States, usually Ukraine’s staunch cheerleader, reportedly lobbied several European capitals against the EU’s Reparations Loan plan. US officials argued the funds should be preserved to secure a future peace deal, suggesting that using them now would “prolong the war”.

European leaders, already wary of US motives following a controversial US peace plan that was seen as favorable to Moscow, rejected this interference. German Chancellor Merz swiftly declared there was “no possibility of leaving the money we mobilize to the U.S.,” emphasizing the consensus that the money must flow to Ukraine. The underlying tension, as reported, is the EU’s fear that the US intends to use the assets to finance Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction primarily through American companies, with Washington potentially receiving 50% of the profits from the venture.

This situation has forced the UK, which holds £8 billion in frozen Russian assets and seeks a stronger security pact with the EU, to consider providing its own national reparations loan while also potentially offering guarantees to the EU’s loan in exchange for access to EU defense financing schemes.

While the prior discussion focused intensely on the Western mechanisms of economic warfare, the Chinese perspective remains anchored in diplomacy and de-escalation.

China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian delivered a sharp response to the European Commission’s proposal to use frozen Russian assets to finance Ukraine, calling it a violation of international law and a dangerous precedent. Speaking at a regular press conference on December 2, Lin stated that

“China consistently opposes unilateral sanctions that violate international law and lack authorization from the UN Security Council”.

Beijing has consistently reaffirmed its position on the Ukrainian issue, urging that “all sides should remain calm and show restraint” and work to “de-escalate the situation through dialogue and consultations”. The stated goal of China is to “create conditions for a political settlement to achieve a ceasefire as soon as possible”. The Chinese spokesman explicitly emphasized that China “supports resolving the crisis through political means and preventing further escalation”

As the December 18 summit looms, the outcome of the grand asset seizure scheme remains highly uncertain.

The proponents, led by the EC and Germany, argue that the Reparations Loan is politically necessary and legally sound, asserting that Russia must pay for the damage inflicted. The EU is betting that by covering two-thirds of Kyiv’s needs, it will gain crucial leverage on the international stage.

The opponents, primarily Belgium, warn that the plan risks global financial stability, could invite capital flight, and that the EC’s safeguards are insufficient against Moscow’s promised “harsh and extremely painful” legal and retaliatory steps. Russia, having elevated the mere discussion of seizure to a potential casus belli, will certainly not take the action lightly.

The fact that the world’s largest political bloc must now resort to obscure “emergency” clauses to pass a financial decision over its most significant strategic challenge, merely because a handful of member states fear the legal blowback (and because one member insists on obstruction), demonstrates Europe’s continuing struggle with unified foreign and financial policy. Whether the EU finally manages to consolidate its strength and use its “golden ticket”—the frozen assets—to gain influence in future peace talks, or whether the plan collapses under the weight of legal anxiety and internal division, is a development we are all keenly waiting to see.

The only thing certain is that whatever decision is made, the price, whether paid by EU taxpayers, Euroclear, or the stability of the Eurozone, will be steep.

Join the Conversation:

📌 Subscribe to Think BRICS for weekly geopolitical video analysis beyond Western narratives