The global race for rare earth minerals has become one of the defining geopolitical contests of the 21st century. These minerals, hidden deep inside motors, turbines, and microchips, are now as strategically important as oil once was. They sit at the core of electric vehicles, wind turbines, guided missiles, F-35 fighter jets, smartphones, and medical imaging machines. Rare-earth permanent magnets, especially NdFeB magnets, are the unseen force driving modern technology. As the world accelerates toward clean energy and high-performance electronics, control over these materials is shaping global alliances, trade policy, and national security strategies.

This month, during the second session of the G20 Summit in Johannesburg, Prime Minister Narendra Modi emphasized the importance of deeper cooperation among G20 nations on critical minerals. He highlighted their role in cleaner energy transitions and advanced technological research, proposing expanded collaborative research and smoother supply chains for these essential resources. PM Modi underscored that global coordination within the G20 is vital to ensure sustainable access and utilization of minerals crucial for energy, technology, and resilience-building initiatives.

Echoing this at the 17th BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro (July 2025), Modi called for ‘mineral security’ within the bloc, urging secure supply chains for critical minerals and warning against any country weaponising these resources for selfish gain.

Meanwhile, this week, India signalled that it intends to be a serious player in this emerging landscape. With the Union Cabinet approving a ₹7,280-crore scheme to build the country’s first integrated ecosystem for rare earth permanent magnets, New Delhi is stepping decisively into a domain long dominated by China.

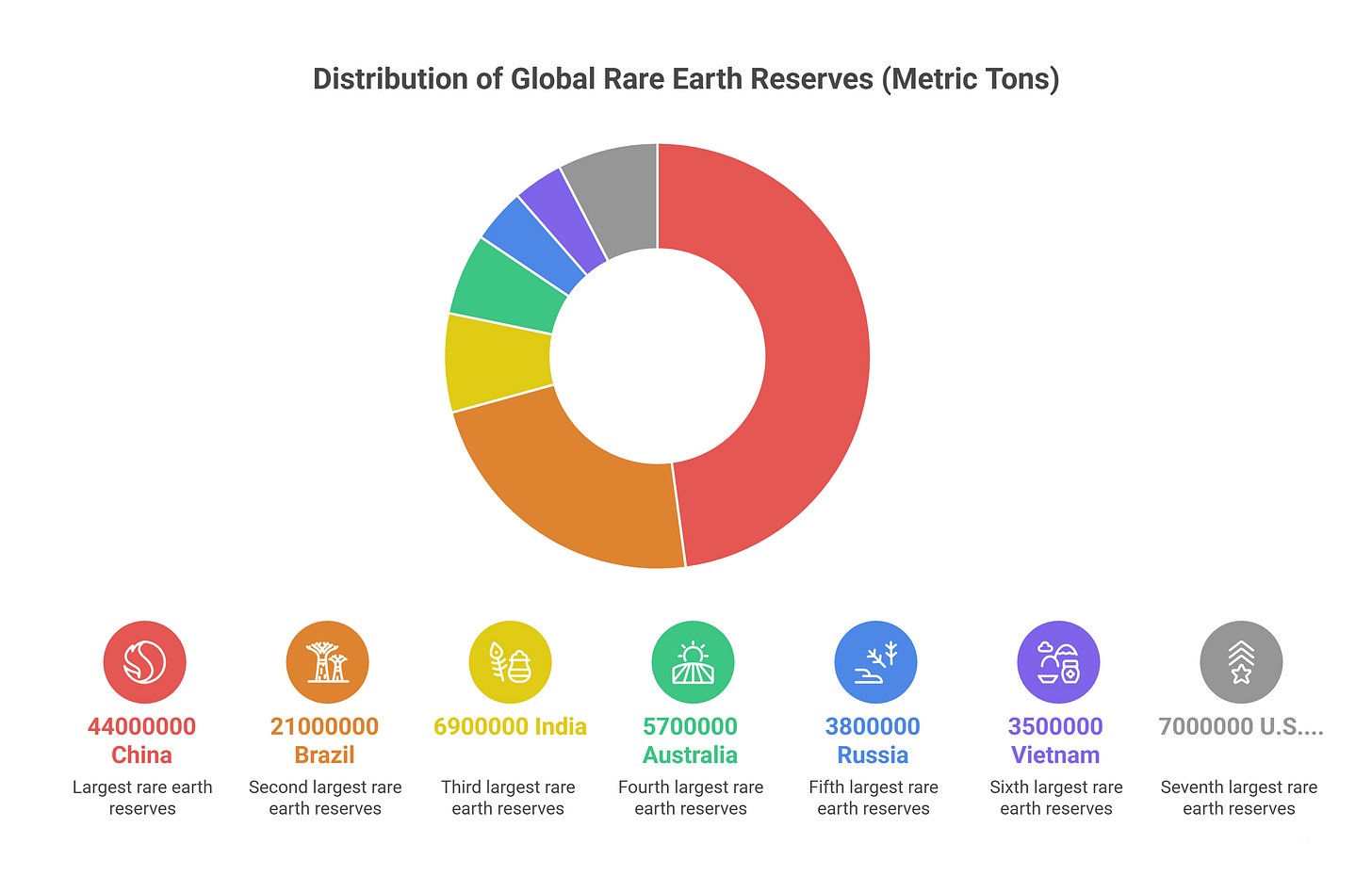

For decades, China has controlled nearly 90% of the global refined magnet output and about 70% of rare earth mining. Its grip over the supply chain has been a point of leverage in geopolitical negotiations, often reminding other countries how vulnerable their growth plans are.

India’s new scheme aims to change that narrative. The government plans to create a complete domestic value chain, from rare earth oxides to metals, alloys, and finally high-performance NdFeB magnets. Around 6,000 metric tonnes per annum of manufacturing capacity will be established, with five companies selected through a global competition.

The programme will take seven years to roll out, including two years for building the facilities, and is backed by a combination of capital subsidies and sales-linked incentives. It is not merely an industrial policy move; it is a strategic shift toward self-reliance in a field that underpins everything from electric mobility to missile technology.

The importance of this initiative becomes clearer when one considers India’s own consumption trajectory. A mid-size electric car requires up to two kilograms of NdFeB magnets, while a single 3-megawatt wind turbine needs around 600 kilograms. As India pushes for 30% EV penetration by 2030 and expands its renewable energy capacity at an unprecedented speed, demand for rare earth magnets is set to rise exponentially. Today, almost all such magnets are imported, mostly from China. Without domestic production, India risks building its green and defence future on an unstable foundation.

What makes this effort even more significant is India’s natural resource base. The country has the world’s fifth-largest rare earth reserves, around 6.9 million tonnes, but contributes barely one per cent of global output. Most of India’s viable rare earth resources lie in the southern coastal states. The Kollam–Alappuzha–Kanyakumari belt in Kerala, the Chatrapur sands of Odisha’s Ganjam district, the Srikakulam and Visakhapatnam coastline in Andhra Pradesh, and the Tuticorin–Tirunelveli stretch in Tamil Nadu are rich in monazite-bearing sands. These minerals contain neodymium, praseodymium, and other rare earths essential for magnet-making. Yet mining and processing remain limited because monazite also contains thorium and uranium, bringing it under strict regulatory oversight.

Processing rare earths is difficult and environmentally sensitive. Isolating the 17 rare earth elements requires hundreds of solvent extraction steps, vast quantities of chemicals, and results in significant toxic waste. Historically, only China built the scale, expertise, and, in many cases, the willingness to absorb the environmental cost required to dominate the supply chain. India’s new programme attempts to build this capacity through modern, safer, and tightly regulated methods, jointly overseen by the Department of Atomic Energy, the Ministry of Mines, and NITI Aayog.

The geopolitical timing of India’s move is unmistakable. China has tightened export controls on rare earth technologies. Europe is scrambling to de-risk its supply chains. The United States is investing billions to revive its own processing capabilities. Japan and South Korea are aggressively diversifying their imports. In this global churn, India is positioning itself not just as a mineral-rich country, but as a future hub of magnet manufacturing—a role that carries technological, economic, and strategic weight.

The scheme also aligns with India’s long-term national vision. Rare earth magnets are the backbone of high-tech manufacturing, clean energy and advanced defence. By developing an integrated ecosystem at home, India strengthens its ambition of becoming a global manufacturing hub under Atmanirbhar Bharat. It also supports the transition to Net Zero by 2070. Perhaps most importantly, it contributes to the government’s vision of Viksit Bharat @2047; a technologically capable, economically strong and strategically autonomous India.

Amitabh Kant, former CEO of NITI Aayog, captured the essence of this shift when he noted that India will “set its own terms” rather than letting global supply chains dictate its pace. In other words, the REPM scheme is not just about magnets. It is about control, over technology, over national security, over economic growth, and over the pace at which India moves into the future.

As the world redraws its mineral map, rare earths have become the new currency of power. India’s latest move ensures that it is not just watching this transformation unfold, but actively shaping it.