By Prof. Andrea Pincin; originally published on November 21, 2025 in the global-politics journal Krisis.info

Summary – Mussolini’s “battle for grain” is now projected onto a global stage. The BRICS+ group – which today accounts for nearly half of the world’s cereal production – has elevated agriculture to a strategic priority, formalizing the creation of the BRICS Grain Exchange. Dismissed with condescension in much of the West, this initiative is in fact among the most radical developments in recent decades in the geopolitics of food commodities. Its goal is agricultural autonomy: price formation in local currencies, reduced reliance on Western exchanges, and less exposure to the US dollar. In doing so, it reasserts the centrality of agriculture and compels Western states to prepare – urgently – to meet this challenge.

On 12 November 2025, during a plenary session of the Russian State Duma, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Patrushev – formerly Minister of Agriculture – reported on the progress made in establishing the BRICS Grain Exchange.

The core idea is to build a trading platform for cereals (and, potentially, other agricultural commodities) among the BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and newer members such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. The purpose is to enable these countries, which produce roughly 44% of the world’s cereals, to set prices independently, reduce dependence on Western exchanges, and transact in local currencies, thereby sidestepping sanctions risks and decreasing reliance on the US dollar.

This is a global re‑enactment of the historic «battle for grain» launched by Benito Mussolini in 1925 to free Italy from cereals imports. Today, however, production self‑sufficiency has been elevated to an international strategic principle.

The project of a BRICS agricultural exchange emerged in March 2024 at the initiative of the Union of Russian Grain Exporters and obtained formal support in the Kazan Declaration of October 2024, where BRICS leaders described it as a step towards a «fair agricultural trade system»

In Western mainstream media, news of the project’s progress attracted little attention, as if insignificant or irrelevant. After all, what weight can be given to such an initiative when Jim O’Neill, the economist who coined the acronym BRICS, has dismissed the alliance of emerging economies by asking: «I’m not sure what the purpose is, other than to be a club that the United States is not a member of»

Even so, the plan to set up a BRICS Grain Exchange has drawn interest from some Western analysts. In 2024, the Council on Foreign Relations – one of the most influential US foreign‑policy think tanks (it included prominent analysts such as Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski and George Kennan) – published an article titled «Why BRICS Expansion Supports Russia’s Grain Exchange Initiative» It highlighted a notable fact: the expanded BRICS+ grouping, now 11 members and 10 partners, represents approximately 44% of global cereal production and 25% of cereal exports. With the inclusion of new partner states, other studies indicate that BRICS+ encompasses 42% of the world’s arable land and about 50% of global cereal output.

This may appear trivial, but – as Krisis has previously argued – it is highly consequential: those who command global agricultural production and markets control autonomy, stability, and power. In just 15 years, global cereal production – and, by extension, humanity’s food security – has become largely contingent on the BRICS+ geoeconomic aggregate.

This aggregate comprises sovereign nations not united under a single flag, not bound by common treaties, nor (yet) sharing a common currency or market. They are independent actors that often compete for their own interests. But they share a defining characteristic: agriculture and food commodities sit at the top of their national political agendas as guarantors of social and demographic stability.

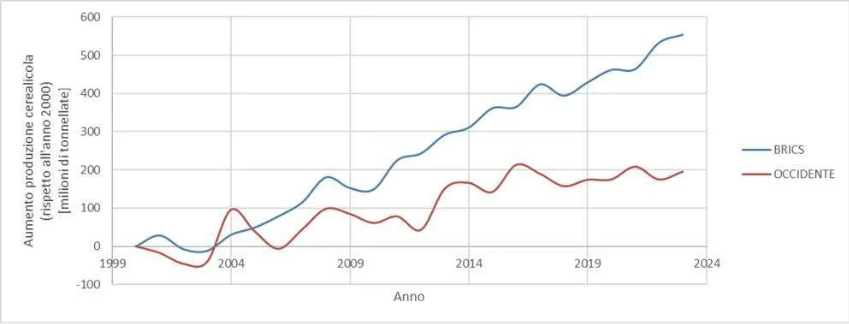

Political prioritization of agriculture has turned BRICS nations into major primary producers, particularly of cereals. FAO data allow for a comparison of cumulative cereal‑output growth in key BRICS states (India, Russia, China, Brazil) versus leading Western economies (United States, European Union, Canada, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand) from 2000 to 2023. As the accompanying chart shows, over the 23‑year period BRICS cereal production growth was roughly three times that of the West.

This reading is echoed by Intereconomics, the academic journal of European political economy jointly published by the Leibniz Information Centre for Economics (the world’s largest economic‑literature library) and the Centre for European Policy Studies. «The BRICS+ countries represent 20% of global agricultural exports» the journal notes, «while the G7 share fell from 30% in 2011 to 28% in 2021»

Beyond the production metrics, it is striking that within BRICS+ some of the world’s biggest producers coexist and coordinate with some of the largest importers of agricultural commodities – paying also particular attention to more fragile Global South countries in terms of food security.

As Krisis previously underscored, Russia and Brazil now control over one‑fifth of the international grain export market, while India has become the world’s leading rice exporter. China, by contrast, is the largest importer of agricultural commodities, closely followed – within the grain sector – by BRICS+ members such as Egypt, Iran, Ethiopia, United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia, together with several partner states including Nigeria.

This distinctive configuration brings together major agricultural (and food) producers and importers within a single grouping engaged in political dialogue and coordination. It affords BRICS+ considerable leverage over international agricultural markets and the distribution of key food commodities, shaping their availability, prices, and payment mechanisms.

Against this backdrop, at the 2024 BRICS+ summit in Kazan, Russia proposed the establishment of the BRICS Grain Exchange. Some analysts contend that this institution «represents one of the most radical moves in recent decades in the geopolitics of food commodities. Its implications touch African food sovereignty, the dynamics of international trade, the status of the dollar, and the role of emerging economies»

The platform of the BRICS grain exchange – now in an advanced stage of development – was initially conceived for the grain market but is being broadened to include other agricultural products. The BRICS Grain Exchange carries multiple meanings and implications. On the one hand, it bolsters food security for member and partner countries, especially in the Global South, by shielding markets from external shocks and speculative swings. It presents itself as an alternative to Western agricultural exchanges such as the Chicago Board of Trade, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and Euronext, which have traditionally set benchmark prices and volatility for agricultural commodities.

It also promotes the adoption of an independent price index for agricultural goods, one anchored more in the internal dynamics of the BRICS+ group and less in the broader international context, particularly the speculation of large financial actors linked to Western countries. The exchange could, moreover, catalyse the development of regional logistics infrastructure dedicated to intra‑BRICS+ trade.

In addition, the BRICS Grain Exchange would reduce the dollar‑denominated dependency of agricultural and food trade, currently predominant even in primary‑sector transactions. It is explicitly structured to enable the exchange of agricultural commodities in local currencies.

In this sense, it becomes a powerful instrument for curbing the dollar’s role in the sector and, consequently, Western speculation and geopolitical pressure – including sanctions – while promoting food security across member states. Furthermore, the new exchange can serve as a laboratory to test a formal trading platform that incorporates alternative financial and payment mechanisms to the dollar.

The consolidation of the BRICS Grain Exchange would redefine the ground rules of global agricultural trade. This scenario – moving beyond neoliberal globalization and re‑centering agriculture within international geopolitics – calls on Western states, particularly the European Union, to prepare swiftly to meet this challenge.

About the Author: Andrea Pincin is a forestry engineers, he heads the Services centre for forestry and mountain farming (CeSFAM) of the Autonomous Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia (Italy). He is also an adjunct professor at the University of Udine (Italy), where he teaches grassland and pasture management. He is the author of the book «La città rurale (the rural city)» edited by Asterios and a contributor to the magazine L’AltraMontagna, where he curates the column «mountain landscape, a meeting ground between humanity and nature» and a contributor to the global-politics journal Krisis.info, where he focus on the strategic role of agriculture, food production, and inland areas in geopolitics and international economic competition. The contributions he publishes are professional in nature and not institutional.

Join the Conversation:

📌 Subscribe to Think BRICS for weekly geopolitical video analysis beyond Western narratives.