The scale of innovation on the battlefield has been insane. If Ukraine had not embraced its numerous defence innovators, but instead imposed additional bureaucratic burdens and worked only with selected industry representatives, it would likely have ceased to exist.

In peacetime, defence accelerators often help identify innovation long before national armed forces or procurement authorities begin paying attention.

NATO has its own accelerator—NATO DIANA—which selects 150 companies from thousands of applicants and provides them with funding, mentorship, and entry into the defence ecosystem. It became operational in 2023 and, as I see it, has been influenced by the war in Ukraine in many ways.

I recently returned from the launch of a new cohort of the NATO DIANA, hosted at one of its sites, COVE in the Canadian city of Dartmouth, where I spent a week with 12 startups selected for the 2026 cohort.

Here is my overview of the NATO DIANA program, including a list of companies I had the chance to network with. If you are in the defence tech world, consider them for your current or future partnerships.

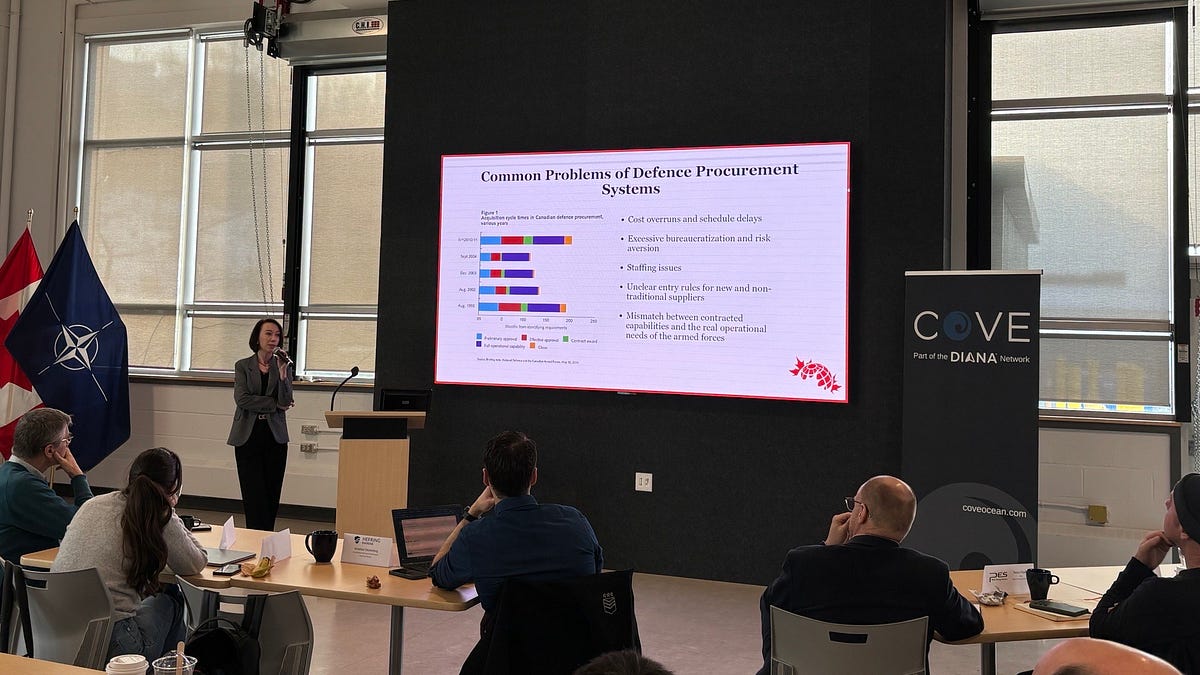

Initially, I was invited by COVE to deliver a presentation on defence procurement sector reforms across different countries (based on my recently published long-read article). I wouldn’t be myself if I didn’t conclude by discussing how Ukraine’s procurement experience is shaping policies in Western countries.

One key lesson: defence procurement systems worldwide have much to learn from Ukraine’s agile approach and its focus on end users who actually have purchasing power.

Since the Russia-Ukraine war remains the only high-intensity interstate conventional war in the world today, it shapes not only procurement processes but also technologies. Ukraine, together with its Western allies, is fighting not only Russia but an entire bloc of anti-democratic states and their combined technological capacities. This makes uniting efforts in collective defence critical.

NATO DIANA aims to identify the most promising innovator companies across the Alliance and help them scale and deliver effective solutions for the armed forces.

I spoke with several parties involved in this accelerator to better understand how the program continues to evolve.

What is NATO DIANA?

DIANA (Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic) is a competitive initiative to help innovators connect with experts, investors, and industry partners to advance and commercialize technologies that address defence and security challenges for NATO members.

It helps dual-use innovation bridge the civilian and defence sectors, as many startups lack defence experience, requiring them to adapt their technologies and models to military requirements.

The program accepts applications from any incorporated company headquartered in a NATO member nation and seeks technology solutions at TRL 4-7.

The selected innovator companies get the following:

-

learn how to prepare their businesses for the defence and security environment and understand how the defence sector actually works;

-

gain early exposure to potential customers;

-

safeguard their solutions and manage a wide range of security risks;

-

access a network of more than 200 specialized test centres across the Alliance, each offering specific technology testing capabilities;

-

connect with a trusted, transatlantic pool of investors to support company growth and learn how to combine public and private funding.

In addition, innovators receive €100,000 in contractual funding and may apply for additional resources for testing, evaluation, validation, and verification activities.

At the end of Phase 1, a limited number of DIANA Innovators move on to Phase 2 of the Accelerator Programme and receive up to €300,000 in additional contractual funding to support a further six months of iteration of their solution.

Participants get access to DIANA’s network of 17 sites and over 200 test centres in NATO’s 32 member countries.

The Challenges

The process at DIANA starts with aggregating demand signals from across the Alliance. As a NATO entity, DIANA is not tied to any single nation, which allows it to look at defence planning processes at the NATO level and identify critical capability gaps and the solutions that could be real game-changers. “Based on a clear understanding of where the most critical gaps are, we evaluate proposals and build a cohort of around 150 companies best positioned to address them,” explained Tom McSorley, General Counsel for the NATO DIANA, in a podcast by the Emerging Technologies Institute.

The key with each challenge is articulating the problem NATO is trying to solve and the outcomes needed, while allowing industry to propose how best to solve it. For instance, here is a description of the Autonomy and Unmanned Systems Challenge for the 2026 cohort.

DIANA asks for short, low-cost proposals that outline the technology, business approach, and intended application. The aim is to identify technologies that offer the strongest solutions while also demonstrating a credible pathway to sustainability — including a path to revenue and eligibility for private investment.

In 2023, DIANA initiated its pilot challenge programs, choosing 44 startups (out of 1300) from 19 countries operating in three key areas: energy resilience, undersea sensing and surveillance, and secure information sharing.

For 2026, the program expanded to 10 challenges, including:

-

Energy & Power

-

Advanced Communication Technologies

-

Contested Electromagnetic Environments

-

Human Resilience & Biotechnology

-

Operations in Extreme Environments

-

Maritime Operations

-

Resilient Space Operations

-

Critical Infrastructure & Logistics

-

Autonomy & Unmanned Systems

-

Data Assisted Decision Making

NATO DIANA and Procurement

“NATO DIANA does not hold direct procurement authority; instead, it has the authority to issue prototyping arrangements with companies selected through its challenge programmes,” shared Mr. McSorley in a podcast.

Through these challenges, DIANA brings innovative companies into the ecosystem and, via its Rapid Adoption Service, works with interested Allies to develop more specific technical requirements – what they would like to see from a prototype. This enables Allies to issue targeted contracts for prototype development and to validate those prototypes.

Also, DIANA operates within a broader NATO procurement architecture. Its partner agencies — the NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA) and the NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA) — both have procurement authority and provide procurement support to Allies on a multilateral, bilateral, and unilateral basis. These agencies can take prototypes that have been validated through DIANA’s competitive process and move them directly into production through single-source procurement mechanisms.

At the national level, there is also ongoing dialogue on how Allies can leverage the competitive processes already completed within DIANA, avoiding the need to run additional national competitions that are costly and time-consuming.

At the same time, DIANA seeks to reduce risk for investors. A core objective of the programme is to encourage private capital to support early-stage defence and dual-use technologies.

2026 Cohort

For its 2026 programme, DIANA selected 150 companies from 24 NATO countries, chosen from a record 3,680 submissions. You can check the full list of the 2026 cohort here.

During my trip to Dartmouth, I met in person with 12 European and North American companies. Many of them focus on maritime operations, which aligns with the capabilities of their hosting site, COVE, an innovation hub for maritime technologies. Additionally, a range of other areas was also represented.

Below is a list of these companies, along with brief descriptions of their solutions. All of them are looking to scale their technologies and explore partnership opportunities globally, and many of their solutions are already highly relevant to the challenges emerging from the battlefield in Ukraine and beyond.

If you identify a potential area of overlap or cooperation, feel free to reach out to them directly—or to me, and I’d be happy to make an introduction.

Alumni Stories

Even before my trip to Dartmouth, I was already in touch with several DIANA alumni companies. They closely observe the war in Ukraine and note that, for any innovator, getting technologies to the battlefield is the most effective way to move forward in the sector.

One of them is Quantropi, a Canadian firm that specializes in quantum-secure data encryption technologies. James Nguyen, co-founder and CEO of Quantropi, shared that NATO DIANA helped Quantropi evolve from a theoretical dual-use technology to concrete defence capabilities ready for procurement. “The direct contact with personnel from a number of NATO MoDs, primes, successful suppliers, and DIANA Alumni was invaluable because it gave us direct intelligence and understanding of what is needed and what it will take to succeed in the defence sector,” James said.

Since February 2025, Quantropi partnered with a Ukrainian company, HIMERA, a producer of dual-use walkie-talkies currently used on the battlefield. This partnership enabled HIMERA to integrate advanced post-quantum encryption into its products. I wrote a separate article about this collaboration here.

Another example is the Canadian company Qidni Labs. Qidni is developing portable blood purification technologies designed to make life-saving treatment accessible to millions of patients with kidney failure worldwide. The company was selected for the NATO DIANA 2025 cohort and has attracted interest from Ukrainian end users seeking solutions for critical care in battlefield and emergency response environments.

According to Dr. Morteza Ahmadi, CEO of Qidni, Ukraine’s interest was not driven by novelty but by practicality. In a wartime environment, technologies that reduce logistical burdens and function in highly constrained settings become immediately relevant. “What Ukraine has changed for NATO innovators is speed,” Morteza explained. “Problems that used to take years to define now take weeks, and solutions are evaluated in real operational conditions. That kind of feedback loop is unprecedented in defence innovation.”

According to Dr. Ahmadi, NATO DIANA lowers the friction between dual-use startups, military end-users, and procurement ecosystems. It creates credibility and access, not just funding. Ukraine-related interest shows DIANA is not abstract; it’s operational.

DIANA Mentors and Experts

NATO DIANA has a vast network of mentors and experts who volunteer their time to work with innovators for 6 months, providing them with valuable advice and connections. For anyone in the industry interested in mentoring, there is an opportunity to apply for these positions through the DIANA website.

One of them, David Tucker, a former Royal Canadian Air Force aerospace engineer who spent half of his career in flight test and the other half supporting Maritime Helicopter operations at sea and ashore, said that he joined DIANA via COVE because he is interested in helping great tech survive contact with reality and get into the hands of operators.

According to David, NATO DIANA matters because the threats are moving faster than traditional defence procurement timelines. It gives innovators a way to get in front of real problems, get tested, and get adopted across allies, without everyone reinventing the wheel.

Another mentor, Brent Newsome, the co-founder and former CEO of Halifax-based NewPace Technology Development, a pioneering telecommunications software company, said that a military start-up accelerator should be an open marketplace where the exchange of ideas, cultures, and domain knowledge is encouraged and celebrated.

“In my short exposure to the companies participating in COVE’s activities, I observed this cycle of learning and exchange of experience in real time. A couple of companies were represented by veterans who provided valuable and critical feedback to companies in other countries run by civilians who had little exposure to military field conditions,” Brent added.

Indeed, I also witnessed that many companies selected for DIANA initially struggled to identify concrete defence applications for their technologies. In many cases, these ideas emerged in real time through brainstorming sessions, peer reviews, and iterative feedback unfolding directly in front of us.

Mr. Newsome added that he wished there had been more uniformed service members present as advisors/observers to provide real-time feedback and to gain exposure to the ideas being presented. “It was a powerful moment and there was a real spark from that conversation, and I am keen to see how the process of exchanging ideas between companies and with end-users unfolds through this cohort,” he said.

Concluding Thoughts

During my involvement with the NATO DIANA program as an external observer, I realized one key thing: it is crucial for defence innovation companies to work closely with end-users. This allows users to actively guide new companies and help them develop viable products that address real-world, rather than abstract, challenges.

Ultimately, armed forces benefit as well, as they receive functional capabilities tailored to their actual needs.

As Artem Pyndyk, a Ukrainian veteran with experience working in a defence accelerator in Ukraine, puts it, “in Ukraine, having a direct link to the frontline is a must-have: visiting training grounds together with your team and engaging with military personnel not only in third-wave coffee shops.”

For companies in Europe, the UK, North America, or Australia, engaging with their armed forces is essential to understanding their demands.

In many countries, this realization has only recently begun to emerge.

In the context of the Russia–Ukraine war, from my perspective, getting involved in Ukraine is one of the best ways for companies worldwide to understand how relevant their innovations truly are and to receive direct battlefield feedback. There are multiple ways of doing this. We also know that the feedback might not always be positive, but it is a necessary step on the path to success.

Among the participants I met, I saw significant interest in engaging with Ukraine. In my personal capacity, I try to leverage my networks across Ukraine, Europe, North America, and Asia to help NATO DIANA innovators develop products that meet the real needs of the militaries in different countries and regions.

In December 2025, it was announced that Ukraine could become the first non-NATO partner in the DIANA program. Reportedly, the parties are already negotiating and preparing a cooperation agreement that would give Ukrainian companies access to Alliance infrastructure and funding.

For Ukraine, getting involved in the DIANA program would mean additional access to funding and unlocking opportunities for Ukrainian companies to reach the wider NATO market.

Read my series of open-access articles “Defence Tech in Ukraine”.